MNC: From shorebirds to conservation

by Oscar Miranda and Noémie Engel

The beginning

Andao, Sama, andao! (Let’s go, Sama, let’s go! in Malagasy) Tamás exclaimed, and Sama dashed towards the funnel trap set up at a Madagascar Plover nest.

It was December 15, 2002, the day they ringed the first bird of that endangered species. Prof Tamás Székely had been searching for decades for an isolated population of shorebirds, and Sama was just finishing his bird monitoring work at BirdLife International under the mentorship of Roger Safford. With the bird in hand, Sama jumped with joy, and from that moment on, Tamás knew they would make a solid team.

Finding the “hole in the rock”

In the following years, they visited almost all the western coasts of Madagascar in search of more individuals. However, after analyzing the data, in 2008, Peter Long, a PhD student of Prof Székely, told them, "We need to go to Andavadoaka." This village, whose name means "hole in the rock," is surrounded by salt marshes, bodies of water, and an extensive coastline. It was no coincidence that it had the highest density of Madagascar Plovers.

Monitoring the area brought an even bigger surprise: they discovered that two other species also shared the same habitat—the White-fronted Plover and the Kittlitz's Plover. The Madagascar Plover and the White-fronted Plover are socially monogamous and both parents take care of their chicks. In contrast, Kittlitz's Plovers have high divorce rates and only one parent looks after the young. This made Andavadoaka an ideal location to study how different parenting styles and mating systems impact the survival and stability of shorebird populations.

Viral Pivot

What followed were ten golden years, during which international and local students, alongside Sama and Tamás, monitored the three bird species. Several research articles were published, a camp accommodating nearly ten people was built, over 5,000 nests were found, and more than 10,000 plovers were ringed.

Everything was going smoothly until 2019, when two events changed the group's history forever. On one hand, the COVID-19 pandemic caused an unexpected disaster: a drastic decrease in foreign tourists in Madagascar. Without tourists, the income that local communities generated through ecotourism—a key component for the conservation of hundreds of endemic species—disappeared. As a result, locals reverted to using environmental resources to meet their survival needs, once again putting the forests at risk.

On the other hand, the plover monitoring team was cut in half. However, taking advantage of the uncertainty in 2020, they decided to search for shorebirds, but no longer along the shores. The forest surrounding the bodies of water had always been there, but only now did the team decide to explore it in depth.

Sitting on a goldmine

At ground level, amidst grass, rocks, and shrubs, they heard the electric and vibrant call of a bird with reversed sex roles, where the female sings to attract the males, who are the sole caregivers of the young. They discovered a remarkably high density of Madagascar Buttonquails around Andavadoaka. Every 100 meters, they found another nest, and another. When they looked up, they realized they were sitting on a gold mine.

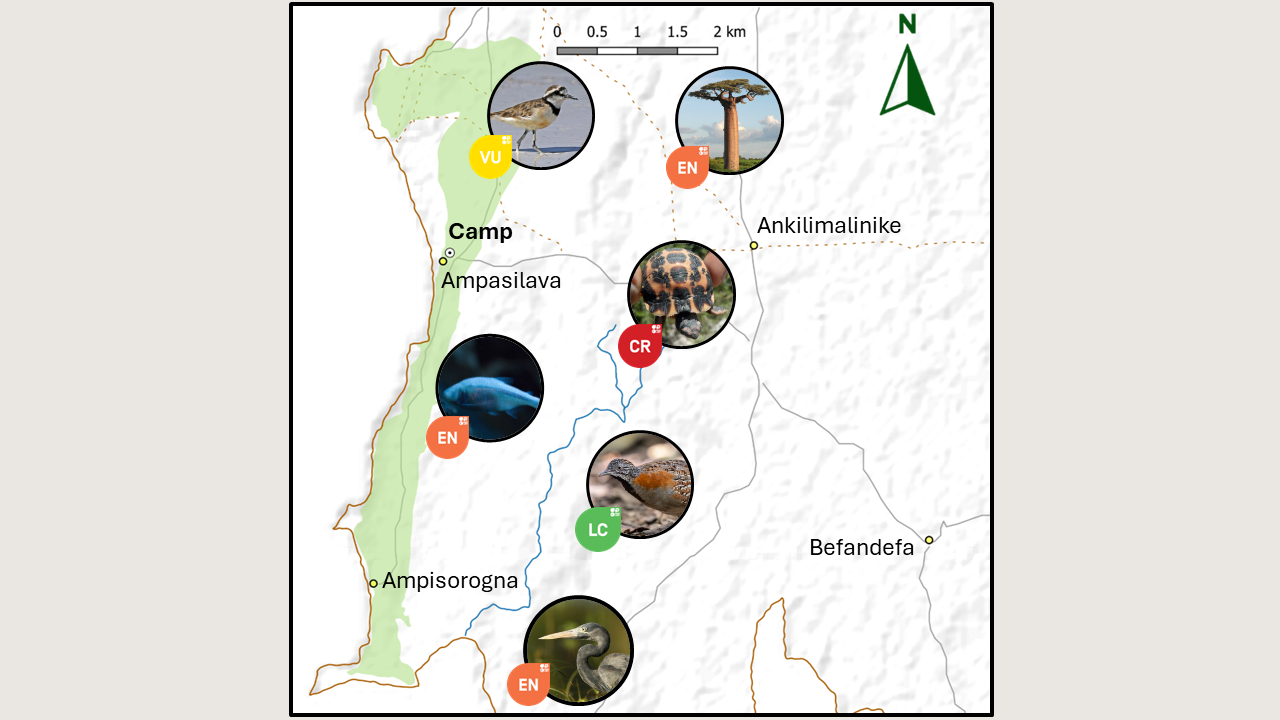

As they reviewed the plover and buttonquail monitoring areas they covered each year, they had a revelation. In this ~80 km² area, at least six endemic and endangered species live: the Grandidier's baobab (Adansonia grandidieri), the spider tortoise (Pyxis arachnoides), the Humblot's heron (Ardea humbloti), a cavefish (Typhleotris pauliani), the Madagascar plover (Anarhynchus thoracicus), and the Madagascar buttonquail (Turnix nigricollis).

It was extremely surprising to realize the richness of an area the size of Istanbul Airport. An area that, if lost, would mean the disappearance of an endemic, unique, and irreplaceable community in the history of our planet. An area that is not protected. An area that needs to be conserved. Now or never.

Andao!

On a cloudy afternoon of November 8, 2023, Tafitasoa Jaona Mijoro, the discoverer of the buttonquails in Andavadoaka; Professor Tamás Székely; Dr. Sama Zefania; and the author of this blog met via video call to form an NGO to address the issue. We named it Madagascar Nature Conservation (MNC), and it was sent for review to the Toliara prefecture. On December 15, 2023, the registration certificate was sent to us from an office 22 km from the site where Sama and Tamás captured their first plover together almost 22 years ago.

Writing this blog nine months after its formation and having had the honor of ringing shorebirds in Andavadoaka, I am pleased to say that MNC has had a very successful field season. Not only did we band hundreds of birds, but we also trained a handful of local students in fieldwork methods. Additionally, as I write this, new members are working on environmental education programs in local communities.

It is true that we have made significant progress towards conserving this habitat in these nine months. However, without a solid structure that provides a sustainable economic alternative for local communities, the baobabs, tortoises, fish, and birds will continue to be at risk. In 2023, tourism returned to pre-pandemic levels. By 2026, it is estimated that 760,000 tourists will visit Madagascar, double the number in 2019. And by 2028, an additional 1 million tourists are expected to arrive on Madagascar's shores.

Good times are ahead. The path is already laid out; all that remains to say is: andao, MNC, andao!

Photos acknowledgements: Dr. Sama Zefania (Luke Eberhardt), plovers (Charles J. Sharp), team 2020 (Sama Zefania), Buttonquail (Graham Gredeman), baobab (Bernard Gagnon), Spider tortoise (Chrysanth H. Mahavilahy), Humblot's Heron (Markus Lilje), cavefish (Wrangel), team 2024 (Jojo Darling). Data tourists: Ministere du Tourisme. Maps and graphs: Oscar Miranda.